Graciela Martínez-Zalce,[1]

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

The border as a television topic

This article analyses how the topic of North American borders has garnered such great interest that television production companies started developing shows that deal with issues which for decades had only been raised in film. Borders are depicted as strategic regions for bilateral relations, be it Mexico-USA or Canada-USA.

One very interesting case is the material produced by the Canadian company White Pines Pictures –headed by renowned documentarian Peter Raymont–, in two different genres: documentary and fiction series. The Border, belonging to the latter kind, is their attempt to present an intelligent, non-conventional alternative for Canadian prime-time viewers, where the aim is to portray border issues from a “Canadian” point of view, i.e., from a seemingly non-judgmental, antiracist perspective.

Unfortunately, it seems that the ideology of the producers is not solid enough to avoid border genre conventions, which emerge in the development of plot topics (terrorism, drug and weapon trafficking, illegal immigration), in the depiction of space via specific landmarks such as border checkpoints or airports, and in stereotyped characters. This leads the narrative into moral solutions that turn out to be both problematic and ambiguous.

Documenting the Mexico-US border: a true-crime perspective on cultural TV

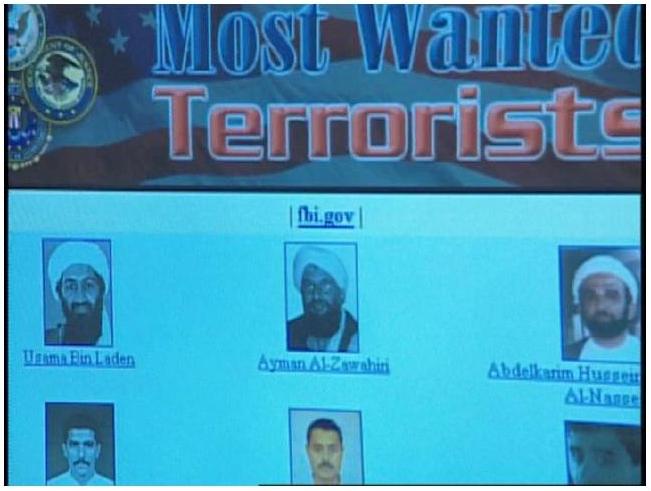

Border wars, a series by NatGeo TV,[2] was launched on January 10, 2010 drawing the highest ratings for a series debut. The very title is enough to get the gist of how this weekly one-hour documentary depicts North American frontiers, mostly the US-Mexico one; moreover, the images on its web page further imply who the enemy is and how this war should be fought: clear blue skies, hills covered with irregular settlements, a fluttering Mexican flag.

The show documents US Customs and Border Protection agents, mainly in the South, waging war against drug trafficking, illegal immigration and, on occasion, terrorism. So, as a spectator, it would seem that these are the most threatening situations for the US. The enemy needs to be destroyed, so patrol cars are equipped with top-of-the-line cameras and monitoring systems controlled by highly qualified teams. They monitor all entries by water and air, but mostly by land, which is the busiest route and, as such, extensively filmed. From the comfort of their living rooms, spectators watch officers patrolling the zone or walking through the Altar desert with devices that detect body heat, looking for illegal aliens, sustaining armed encounters, dismantling vans in search of drugs, detaining suspects at airports, inspecting mail and opening envelopes seeking for pills.

Titles are blunt and forceful and they deal with the main topic of each episode, which is constructed with short action scenes where the agents are the heroes and the villains are dealt with in the same tone –that of criminalization– whether they are smuggling drugs or they are poor peasants looking for a better job. So, there are episodes where the main issue is the hunt (Blackhawk Cruise, Night-shift Preview, Desert Sweep); others where migrants are the focus (The Human Stash, Midnight Runners, Lost in the Desert, Human Assets); others where the most important activity is investigation (Fake Documents, Big Money Bust); a few ones dealing with terrorism (Explosive Search); many more related to narcotics (Drugs Bust); and all of them from the point of view of the very much needed defense (The Big Fence, Road Sweep).

One might wonder: is this cultural TV? Is this scientific research on the subject? At least for Mexican viewers, it is haunting to see how our fellow countrymen and women are being hunted like animals, charged with all kinds of felonies, while the filming crew witnesses brutality in the name of security making us onlookers too.

Julian Gorodischer states, from a Latin American point of view:

[…] la TV antropológica acompaña el rediseño planetario deviniendo menos en testigo de los sucesos naturales del amplio mundo que en un militante a favor de una causa nacional: órgano de política exterior que, independiente de una administración puntual –en la demócrata época de Obama–, cierra filas con otros grupos noticiosos, como la CNN y la Fox News, para encarar una construcción centrípeta y paranoica del relato. (Web)

It is also disturbing to read the cheering comments on the series content, where viewers favour not only the defense that the CBP makes of the US Southern border, but also, of course, the building of the fence (or “el muro de la vergüenza”, as it has been called in Mexico).

The other North American border, changes in the 49th parallel

The border between Canada and the United States can perhaps still be called the longest undefended one in the world, but things have certainly changed. As of January 2008, Canadian citizens need to carry a passport when crossing into the US, for instance. As Konrad and Nichols state, since 9/11, this region has changed more than it did during the entire 20th century, but because of the very intense and important economic interaction between both nations, border security has to “make it possible for our two countries not only to coexist, but also to prosper constantly.” (7)

For decades, the US-Mexico border has given rise to a body of films large enough to be considered a genre[3]. But not many have portrayed what happens along the US-Canada border. Aside from Norma Bailey’s Bordertown Cafe, or Bruce MacDonald’s Highway 61, a road movie with an important border content, it is mostly US films –like Canadian Bacon or South Park, Bigger, Longer and Uncut– that could be included in the genre.[4] All of them share some characteristics, like irony and black humour.

Somehow, television turned out to be the medium that reflected, for the first time, the evident contextual transformation. But this has not taken place, as would seem obvious, on newscasts, documentaries, or products like the National Geographic show.

In January 2008, making the most of the writers’ strike, while US channels were only programming reruns, the CBC at last decided to premiere the police drama series called The Border. Back then it was only broadcast in Canada, but with the first and second seasons already on DVD, and the third one about to appear in that format, it has now been sold abroad.

Because of its large budget, its fast thriller rhythm, and its international aims, The Border has been considered Canadian public television’s big league debut, “but with a conscience” as executive producer Peter Raymont has stated. And I would like to focus on the issue of what this conscience means in terms of the narrative.

Creative sources: White Pines Productions and Canadian public television. A different approach to border matters?

The production source: White Pines documentaries

Two sources can be detected in the show’s design which, in my opinion, are fundamental for the nuances of conscience or morality imbued in the narrative of The Border.

The first one is the documentary work of Raymont and Lindalee Tracey.

This team started exploring the subject with their noteworthy Invisible Nation (1997), where they closely follow immigration officers, trying to answer questions about migration and illegality: a very complex topic involving not only legal matters, but also challenging life experiences. The portrayal of such complexity relies on showing earnest attitudes and actions taken from both sides, migrants and officers. Why do I consider this one hour video produced by White Pines for Canadian TV so remarkable? The reason is it exposes the case for illegal aliens in Toronto while approaching the subject from a very critical perspective.

We listen to a telephone conversation while looking at a blue screen: Ring tone. Ring tone. Immigration. Then, a voice reports illegal aliens. A shot from the shore of frozen Lake Ontario opens and the iconic CN Tower comes into view, locating the characters in Toronto. A female narrator ends this prologue talking about the invisible nation. Afterwards, all the input from the narrator will be poetic and will give voice to a collective “us”, which as constructed by the narrative, should be interpreted as “the Canadians”. She will also be our guide throughout our discovery of the system that prevents unwanted individuals from staying in Canada. The construction of this “us” is meant to engage the spectator looking for a response to the situations lived by the real-life characters.

We will immediately be presented with the film’s plot line; from inside a patrol car, a conversation between two migration officers is documented; they have to arrest a Russian family with three girls and a boy. The narrator states: “They don’t make policy, they simply enforce it”. As we will learn, the protagonists are part of a group of 36 migration investigators from the Toronto area: a white officer who is new to migration, but used to be part of the RCMP, and his partner, a migrant from Guyana and former teacher who has been an officer for ten years. In order to enforce their warrant, the police help them by using violent means: they break windows and doors in order to irrupt inside people’s homes. The mother and children will finally be deported, because as the officer states: “criminals hide better than mothers and children”. The spectator now witnesses the underlying ambiguity in the officers’ duty: they have to treat illegal aliens as criminals, but as the narrator has informed us, they are just following orders.

While panning through rows of file cabinets, we gain knowledge of how the law turns people into statistics, guided by the voice-off: “Here’s the bureaucracy, enforcement headquarters, where illegal lives are stuck into files, where the trials of conscience begin”. Once more, the visual metaphor underscores the dehumanization of the bureaucratic processes while the spoken text stresses the fact that “justice” is not a synonym of fairness.

We will learn that approximately 300 telephonic tips were received each week. Although the white officer thinks tips are useful, the one from Guyana feels “it’s like people ask us to get rid of garbage” and he is quite sure that “man is a perpetual immigrant… if it weren’t for that immigrant, the world wouldn’t be what it is today”.

With a dolly over the railroad, the voice-off narrates the history of migration in Canada, superimposing antique sepia or black and white photographs of migrants constructing that same railway, but also working the fields and attending schools. The nostalgia built by the photographs is interrupted by the situation lived by migrants in the nineties, when the narrator brings us back to contemporary realities: “Now they’re weeded out […] a more cautious welcome, but still they come, the unwanted ones”. A chain of still images of men and women posing in the same garden in the city, men and women from very diverse origins, classes, trades or professions, is an overt statement made by the documentary in favour of multiplicity as a vital component of Toronto.

“Living, hiding, looking like us, perhaps they are us, our own immigrant ancestors […] continuing their journey home, perhaps they are not us at all”, the nostalgic, critical, poetic voice-off states.

There are other collages of contemporary moving images like shots of people of different ethnic origins or ages walking down the streets, while the narrator says “borders can’t withstand the force of hope”. Sometimes, the effect is achieved through old photos complemented by a text that reminds us of the origin of multiplicity: “we came here as dreamers and imagined a nation”. These collages symbolize the Canadian mosaic, illustrated with real human beings that the spectator can identify with.

The documentary also describes the re-bordering processes in the shadow of the security needs of the US. The voice-off explains that “America’s war on crime sends criminals across the border; Canada is at the mercy of geography”, such that it becomes a good place to hide because of the open border. To illustrate this argument, the documentary also shows another team of officers who chase real criminals such as drug dealers, child molesters or men who have committed fraud or armed robbery. (“We are a very compassionate country and that is something we should be proud of […]. They should scrutinize everyone who comes into the country so no one falls through the cracks”). These offenders have crossed the border illegally, abusing Canadian hospitality. We witness not only the chase, but also searches for papers inside these people’s homes.

“The law”, states the voice-off, “must be served with detachment”, because, as the video allows us to see, there is a huge difference between arresting criminals and rounding up families that migrate for economic reasons and who are willing to work and live according to Canadian laws.

Factory raids are presented by the narrator as another necessary evil given the rise in the employment of illegal immigrants. “They are spreading fast in our economy, working long, cheap hours, like we did when we first came here”, the voice-off states in discomfort, as we watch migration officers question themselves about the fairness of the situation. It seems detachment is not always that easy. In these scenes, migrants are the obvious victims being taken advantage of by their employers because they cannot demand their lawful rights or complain. “We pocket their dreams, indulge our own greed, what protects them from us?” asks the narrator once more.

So, at this point, the documentary has reached its goal: letting us know that illegal migrants are not criminals and that officers with a conscience have a very difficult task to perform.

The story of José and Lucy embodies these cases as we listen to their account in Spanish. Once more, the lack of English subtitles is purposeful in order to make a statement. We meet José, his back to the camera, mopping an aisle. José cannot show his face because he has no papers, the visual metaphor says. They belong to those who arrive at Canada either because they are poor or “they are afraid, they wait quietly for miracles”. This Uruguayan couple has three children and is expecting their fourth. They had to flee their home country because José was a policeman and someone was looking to kill him. Lucy was a medical intern. In Canada, both of them hold cleaning jobs. Their underemployment is classified by the narrator as part of the “crimes of hope in open faces”. When José is arrested and taken to the detention centre, Lucy’s opinion is that maybe there is some undeserved discrimination towards immigrants since they have worked for every little thing they have. Visually, the film emphasizes the lack of hope for these impoverished immigrants with clear metaphors: the aisle José was mopping darkens and he disappears from our sight.

The story goes on in its hopelessness. Bails are expensive, but they make it; still, José can be deported. Then, the scene becomes hurtfully ironic. A POV shot from a swing, in a beautiful green park, while a girl’s voice sings “O Canada”. José is talking about the future of his Canadian-raised but not born, and thus illegal, children. In the next shot, the whole family walks away from the still camera, while the narrator reflects “to live invisibly, imagine the weight of silence” as they vanish from our sight once more. The next we know is that Lucy, who is not eligible for health care, has delivered: “Here’s hope, a child who is Canadian”.

But the end is uncertain and I would dare say, not optimistic, since the cold has returned and we are again, coming full circle, on the other shore of the frozen lake. The narrator concludes that the invisible nation is gray, like winter: “dividing our hearts, do we push them out or leave them, in the shadows?” Can immigrants gain visibility at some point without it being dangerous for their status? The documentary does not provide an answer.

The Undefended Border (2002) is closer to the spirit of the fiction series that will follow, and less critical than its predecessor, because of its less personal, more “objective” tone. Written by Tracey and directed by Raymont, their production is a more conventional series of three, one-hour episodes. The focus is on Canadian Immigration officers and RCMP special task force members and their work after 9/11 in response to US criticism regarding the porousness of the Canadian side of the border.

The structure of every episode is the same: they focus on one specific part of the immigration officers’ work and the action scenes are supplemented with an insight into the characters’ lives ranging from their opinions about cross-cultural training and multiplicity, to their day-to-day official activities and polite professional attitudes. During these scenes subtitles sometimes provide explanations about procedures as well as statistical information about illegal migrants, refugee claims, raids and other related topics. These subtitles are a way of avoiding the nuance of authority that a voiceover would provide. The prologue of each episode, however, does have a male narrator talking about the current intensity of migration and asking: “Who do we want?” “Who do we want to keep out?”

Contrary to the overall content of the episodes, the way in which the presentation is edited gives an impression of violence and thrill, which of course immediately makes us think of police dramas.

It seems important to stress that in every episode, at least one of the immigration officers in the force mentions belonging to a family that migrated legally to Canada. This is undeniably meant to propound the idea of a task force where there is no possible racism, of a country that welcomes migration so warmly that migrants are proud to be migration officers. And there is another set of characters: those who are either welcomed or detained at the border. Subtitles are also used in these cases, letting the viewer know the fate of each one of them.

The series begins with Toughening the Border, where the protagonists are those who check the documentation upon the arrival of foreigners and who think that, in the sake of safety and security in their country, the “wrong” people need to be kept from coming in. Therefore, toughening up Canada’s undefended border is necessary. As we hear them express themselves, it seems that alert becomes synonymous with suspicious and lacking trust. The story tells that training is important, but so are gut feelings. And it is impossible for the spectator not to notice some kind of bias amongst officers: they mistrust people who come from certain geographical areas; they associate class with innocence or “guilt”.[5] These officers make the point that after 9/11 they have to keep their eyes open to distinguish between good guys and bad guys. The dividing line in their lives is not only the physical border they defend, but the distinction between those who live by the law and those who do not. Their aim is to keep Canada safe, the terrorists out, and the border open.

The second episode, Immigration Task Force, documents the activities of a group of migration and RCMP officers created in 1994 to find and catch criminals who are in Canada illegally. This group responds to anonymous phone reports made by Canadian citizens based, we are left to conclude, on suspicion deriving from race and nationality (“A lot of people making assumptions”, states one of the officers). Now that this former “gate” has been transposed, as many as 100,000 illegal migrants have settled in the Toronto area and they have to be caught.

The last one, End of the Line deals with the final part of the process: deportation. The officers here work in factory raids detaining illegal workers who, paradoxically, as one of them states, are doing jobs that no one else would want to do. They also look for war criminals suspected to have links with terrorists because, as they say, one is the means and the other is the end. But as the episode goes on, we learn that many of these men and women are among the 25 thousand so-called failed refugees: people who claimed for refugee status but had it denied and decided to stay in Canada. Given that people who claim that being sent back home would put their lives in danger cannot be deported, some of them stay. One of the court officers interviewed maintains that the Immigration Act should be changed because it grants too many rights to all residents, some of whom have committed crimes. So, we witness people being wrongfully or rightfully detained. Some accept their situation with resignation, but explain why they would rather stay: most want to have a better life. This last episode shows how the “fortunate” removal from Canada is sought and ends with an eloquent epilogue by a female officer, a migrant from Scotland herself: what they want is not to stop people from coming, but having more control on who is coming.[6]

The ideological source: CBC, its mandate and quality programming

The second source in the series design is linked with the CBC’s mandate that defines the corporation as “a content company”. Its vision is defined as: “Connecting Canadians through compelling Canadian content”; its mission: “To create audacious, distinctive programming”, that is meant “to inform, enlighten and entertain”; and among its values: “Serving the Canadian public”.

The CBC’s participation in the very expensive production and broadcast of The Border is important because it gives credibility to the social contribution of the series. In its website, for example, we can find serious articles related to topics like migration or problems with the US.[7] And even though the main objective of the series is thrill and entertainment, the aim exists to create awareness around the issues of immigration policy and national security, from a “Canadian”, as we had already stated, non-judgmental, antiracist point of view.

Toronto, the border town

All the characteristics above are discernible in the plot, characterization, leit-motifs and organization of the episodes of The Border. And protagonist James McGowan says: “The couple’s strong beliefs about human rights issues significantly shaped every aspect of The Border”.[8]

When stories about terrorism, drug dealing, money laundering, human slavery or human organ sales are being told, irony and black humour (traits that have been quite relevant in Canada-US border movies) have to be left behind, it seems. The tone of the series is quite solemn. If the producers had kept human rights in mind at all times, easy answers or black and white solutions to the characters’ dilemmas would not be readily found. However, this sometimes happens and, as the series develops over time, we find stereotyping, judgmental attitudes towards US politics and a trait we had already seen in Toughening the Border: equating alertness with suspicion.

The plot revolves around border problems which an elite group of agents from the Immigration and Customs Security (ICS) Bureau at Toronto have to resolve. Their leader, Major Mike Kessler, “the moral center of the show”,[9] is the protagonist, and almost the only character with a private life in the plot. He has a lawyer ex-wife, who works with NGOs that help people with immigration problems. They share custody of a rebellious ingénue, a well-meaning daughter with a leftist liberal perspective and political inclinations that get her into trouble, always compromising her father’s work.

Kessler also has two antagonists. One is Andrew Mannering, from CSIS, a true villain because he is a Canadian that works to protect US interests. He will reappear in the second season, only now working for a mysterious and infamous private consultant for the Canadian government with obscure connections to US enterprises. The other is Bianca LaGarda (Sofia Milos), US Homeland Security Agent, who will disappear at the end of the first season because of health issues that will redeem her and make her believe in the Canadian health system.

There is a recognizable pattern in the organization of the series. One program deals with domestic issues, the following with trans-border problems. The American (sic)[10] star appears only in the latter ones and judgment becomes part of the content. The geopolitical line is not the only thing that confronts the characters, there is an ideological frontier, too, which is just as important for the development of the narrative.

The presence of the American (sic) agent interferes with the work of the Canadian officers because of the inflexible and incessant requirements of US borderland security regarding how to treat suspects and investigate incidents. In the case of LaGarda, she ridicules the way Canadians focus on problems as she thinks it is naïve, or even stupid. Meanwhile, the Canadian protagonists turn political, social and environmental dilemmas into moral ones, because solving some problems can unleash consequences which are, sometimes, even worse than the original situation, and a fundamental feature of the plot is focusing on doing what is right.

Let us examine, for example, the first episode, called “Pockets of vulnerability”. The edition of the initial scene has a quick tempo, with short shots of landing strips, airplanes arriving, traffic signs, vans parking, officers showing their badges, document checking points, close-ups of passengers, face recognition software. While the suspects are being followed and detained, short shots from different angles are edited and then the scene continues with an on-shoulder camera, both techniques highlighting the thriller/action atmosphere.

The interest of the producers in human rights has been mentioned before; this is an issue without easy answers and it does not lend itself to black-and-white solutions to the characters’ dilemmas. In the episode we are discussing, a Canadian citizen of Syrian descent falls victim to racial profiling. While traveling on an airplane, he sits beside a real terrorist and, because a surveillance camera catches him receiving a note from the criminal, he is taken aside for interrogation. The man is a respectable high school teacher and a family man. But once he has been flagged, he is perceived as a menace to Homeland Security and CSIS. As a consequence, the ICS cannot refrain from investigating the man. At this point the man has been removed from Canada and deported to Syria (the country he had fled from for political reasons), violating his human and citizen rights. Even though it is not a certainty, some hints let the spectator believe the man is not guilty.

Was he signalled out just because he was talking to the wrong person (a suspected terrorist) at the wrong time, or did the misunderstanding take hold because of his looks, origin and religious beliefs?

The plot leads the spectator to ask questions concerning immigration policies post 9/11. Are Canadian immigration officers being forced, because of US paranoia, to do race profiling and act under racial prejudice?

Although the general impression says so, every detail the ICS team finds out about the professor, simple everyday things like teaching chemistry, attending a mosque, taking care of a brilliant student, buying a car, makes him seem more like a suspect. His actions, his relationships, as long as he moves within his religious or cultural community, do not clear him. In the end, right prevails and with pressure from the media and good work from the team, the man is brought back home.

But paradoxically, for a series with an interest in human rights, in respecting differences and condemning Homeland Security policy, Muslims appear as suspects in many episodes.

Guns, explosions, car chases and much running all are part of the action. GPS tracking, cybernetic investigation, hacking, phone calls involving orders from the top, autopsies, these are all part of the procedures followed by the team. It is police drama at its best with a touch of heterosexual tension between some of the characters. The locations are airports, border entrances, hotels, ports, as well as the wilderness that is still a prevailing setting along the US-Canada borderline.

So in its depiction of space, in the topics chosen for the plot and in the construction of characters, the series falls within the characteristics of the border genre: the locations are the expected emblematic places where there are migration and customs officials, flags from both countries, signals of delimitation. There is also stereotyping: Canadian characters act and think one way, Americans (sic) in another, often not good, one.

And that is why I find it interesting to analyze the finale of season 3, which aired on January 14, 2010, just six months after the Canadian government announced that Mexican citizens would need a visa in order to visit Canada, making Mexicans suitable characters for the series’ plot.

It is titled “No Refuge”. Hugo Fuentes, aka “El Carnívoro”, “The Carnivore”, (“That can be no good”, states the computer geek), capo of Los Zetas cartel, arrives at Toronto from Mexico City. Apparently, he is there to close a drug distribution deal in Canadian territory with members of the Mara Salvatrucha.

Ramón Esteban is a Mexican journalist who has sought refuge because his life has been threatened as a result of articles he has written about drug cartels. Killing Esteban is the real reason why Fuentes is in Canada. Esteban is also Major Kessler’s ex-wife’s boyfriend, a coincidence that weakens a plot that was already undermined by stereotyped Mexicans.

Within this framework, obsessions that have been characteristic of the narrative definition of the US-Mexican border are now transferred to Canada. Drugs had never been important as a topic in the show, but when they appear, they are related to Mexico and Mexicans. This is reinforced through the images popping on the screen: the presence of Mexican illegal workers, depictions of maps of Mexico and criminal folklore, like images of “la santa muerte”.

This series purports itself as a production with an antiracist spirit and a focus on human rights. However, two clear examples that challenge this notion can be found in this episode that unravels through long sequences inside interrogation rooms. The first time agents interrogate a Mexican, the character is Carmelita Sánchez, a drug mule. The fact that the diminutive form of the name Carmen appears in an official document such as a passport is quite far-fetched. Carmelita is used an affectionate nickname. The character is built upon the features that US media have given to the stereotype of the Latina gang members.

In another scene, two young men, linked to the Maras and whose family is staying illegally in the country, are also interrogated. At this point, I think it is important to insist that the show had been designed to emphasize the importance of human rights in the immigration process, the difference between Canadian and US investigation tactics, the moral conscience of Major Kessler. On other occasions, Major Kessler bends the rules in the name of the greater good and to achieve justice. So the audience might feel rightfully confused when they witness ICS agents using tactics like intimidation and extortion to obtain information; when Canadian officials threaten teenagers with deporting their whole family, jail in Mexico, and letting the Maras know they have betrayed them. To top things off, when Fuentes is arrested, the fury of his gunmen showers the streets of Toronto with a storm of bullets.

The problem with using contextual references in a fictional narrative is that they make the spectator read them as “documental”. In a series that has claimed to instil a moral substrate in the creation of its characters, the producers should be more careful, for example, with their casting. For a viewer who can distinguish accents in spoken Spanish, it is clear that maybe only one of the characters is convincingly Mexican: some of them are American Latinos, some others are not fluent in the language or do not even seem to be able to speak it, and the only “good” Mexican, the journalist (the only tall, white one), sounds anything but Mexican when, to add a touch of credibility, he speaks Spanish. The conclusion might be that for people in charge of casting, all Latinos look and sound the same.

Poor results and poor reception

Thus, the border zone is depicted not only as conflict ridden, but also as blurry. The constant presence of US forces in Canadian soil, in the name of international cooperation, which, according to the show, is unequal, poses the question of US impositions on security matters as one of the series most important thematic lines.

That is why some reviewers were very critical about the series; and maybe that is why domestic audiences never favoured the show, which was aired in prime time.

Robert Fulford wrote: “There we have the difference between Americans and Canadians, as defined by CBC television. […] The Border […] is the kind of show that makes you proud to be a Canadian –especially if […] you’re also really, really boring. The script expresses […] the ‘sanctimonious, opportunistic anti-Americanism’ that crops up so often among Canadians”.

Justin Podur stated: “The propaganda of ‘bad guys’ and ‘evildoers’ is itself a tool of war, and the CBC’s new show is such a tool. […] Casting immigration agents as action heroes fighting fictional threats covers up what they really do. […] They are bureaucrats who deport people. […] For all it seeming moral complexity, “The Border” thinks it knows who the bad guys are and thinks it knows that they aren’t us”.

So, to reviewers, the first fault of the show is that (as does the entire border genre) it tends to stereotype. And it does it, first, in a way that has been related to the now canonical works that define Canadian identity:[11] Canadians are different than US citizens; but it goes one step further, meaning that different might be read as better. Indeed, sometimes the feeling after the episode is that Americans are bad when compared to Canadians.

Clearly, the fact that the show has roots in documentaries and that it also feeds on its context is something that should be kept in mind and must not be set aside. In 2005, for example, the Canadian Council for Refugees published a review of the Anti-Terrorist Act, displaying their concern about “discrimination in both law and practice, in the area of anti-terrorism measures”, because, as they state, in Canada:

[…] there has been a widening gap between the rights of citizens and non-citizens, as the security agenda is pursued. The preference for applying immigration rather than criminal law measures to suspected terrorists in itself points to a double standard, since immigration measures by definition cannot be used against citizens. Furthermore, Canada’s immigration security provisions impose serious penalties, including deportation potentially to torture, on non-citizens for actions or associations that are completely legal for citizens. (2)

Why do the politics behind the series seem blurry? Because, even as it criticizes US Homeland Security measures and the Canadian Government’s alignment with some of them, it still portrays certain ethnic groups as suspicious, as the immigration officers in the documentaries explained to the audience. Reem Bahdi explains that in Canada the debates “in the context of the War against Terrorism focus on whether Canadian society can morally, legally, or politically condone racial profiling” and illustrates the context:

Within weeks of 9/11, then Premier of Ontario, Mike Harris, announced the formation of a special police unit designed to track down and deport illegal immigrants. While Premier Harris did not explicitly indicate that Arabs or Muslims would be targeted, he did report that the unit’s focus would be to prevent terrorism through deportation, thus leaving little doubt in anyone’s mind as to the ethnic or religious identity of those who would receive special scrutiny. Around the same time, 48 per cent of Canadians reported that they approved of racial profiling. (295-296)

These contextual issues appear as an important part of the show, but it still begs the question: Isn’t all this against the spirit of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which expresses that everyone (not just citizens) has the right of freedom of conscience, religion, thought, belief, opinion and expression (including the press and media), of peaceful assembly and association?

Some episodes and some more general plot threads that run through the show seem contradictory because, while focusing on the obvious possibility of making “honest” mistakes in the pursuit of safety while also defending a fair Canadianness versus US totalitarianism, the writers construct characters based on, I would dare to say, some sort of racial profiling that singles out the appearance of Muslims, Eastern Europeans, and towards the end Mexicans, as either suspicious or guilty.

The leading characters are neither convincingly heroic nor highly moral. In order to achieve their lawful goals, they abuse suspects, many of them who are not citizens, and sometimes they use methods that are clearly against their human rights.

Maybe the influence of the corporation’s mandate was too heavy a burden for the script writers of a police drama which should have heroes instead of moral guides. If the Canadian content seems too biased, and the characters are not only interested in serving the Canadian public, but also in making political statements, the agenda of enlightening and informing is more obvious than the entertaining one (which probably to critics should be the most important).

Maybe the development of what McAllister (2008) calls the new genre of the geopolitical complicity drama, to which I believe The Border belongs to,[12] creates confusion in the spectators and does not fulfill their action expectations. In any case, it does not seem to have successfully worked, since on March 22, 2010 the cancellation of The Border was announced before the bad Mexicans were caught.

Endnotes

[1] The author wants to thank the anonymous reviewers for their sensible suggestions in terms of content and form and to translator Carolina Alvarado for her expertise in rewriting this essay.back to text

[2] In Mexico, it aired on February 3, 2010, with the Spanish name Frontera: zona de peligro.back to text

[3] Regarding the border film genre, the most important works are those by Norma Iglesias and David Maciel.back to text

[4] For a filmography on North American border films, see Graciela Martínez-Zalce, “Borders North of the Americas: Transcultural Spaces of Changing Identities”, International Journal of Canadian Studies/ Revue internationals d’études canadiennes, 27 (2003): 229-253.back to text

[5] In one scene, a female migration officer, after interrogating a woman with a Russian passport states she will have no problem because she comes from money, she knew how to present her papers and she was prepared.back to text

[6] The agenda in the documentary might be that of the necessary evil; in some cases, toughening might seem contrary to a humanitarian view of migration, but it is necessary due to people using fake documents, lying, committing criminal offences, or abusing refugee claims.back to text

[7] McAllister studies similar issues related to the mini-series called Human Cargo (2004).back to text

[8] “The Border eagerly anticipated series premieres as American shows are in reruns”, Note from The Western Star, 05/01/08.back to text

[9] Idem.back to text

[10] In the second and third seasons it will be actress Grace Park.back to text

[11] Works like the ones published in the seventies by important authors such as Margaret Atwood and Northrop Frye.back to text

[12] This is more widely explored in my forthcoming book Instrucciones para vivir en el limbo.back to text

Bibliography:

“The Border”. Summary. tvrage.com. Web. 31 March 2008.

“Fireworks International Takes The Border Stateside”. contentfilm.com. Web. 27 February 2009.

“ION Has Their Eye On Canada with Border Sale”. tvfeedsmyfamily.blogspot.com. Web. 25February 2009.

“More security, no more safety”. The Leader-Post (Regina). Web. 25 Feb. 2008.

“No Refuge”, The Border, episode 12, season 3. sidereel.com. Web. 12 Feb. 2010.

“Raymont makes leap into drama with The Border”. cbc.ca.Web. 7 Jan. 2008.

“The Border eagerly anticipated series premieres as American shows are in reruns”.

The Western Star. Web. 1 May 2008.

“The Border has found its place in TV land”. The Calgary Herald. Web. 31 March 2008.

“The border”, cbc.ca. Web. Feb. 2009.

Adelman, Howard. “Canadian Borders and Immigration post 9/11”. University of Wollongong. Web. 27 July 2010.

Andreas, Peter, Thomas J. Biersteker. The Rebordering of North America, Integration and Exclusion in a New Security Context. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Bahdi, Reem. “No exit: Racial Profiling and Canada’s War Against Terrorism.” Osgood Hall Law Journal 41.2.3 (2003): 294-317. Web. 27 July 2010.

Border, The, seasons 1 and 2. Peter Raymont y Lindalee Tracy, creators, Prod. White Pine Pictures & Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2007, 2008. DVD.

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Part I of the Constitution Act 1982. Web. 27 February 2010.

Canadian Council for Refugees. Closing the Front Door on Refugees. Report on the Fist Year of the Safe Third Country Agreement, December 2005. Web. 27 July 2010.

Canadian Council for Refugees. Non-Citizens in Canada: Equally Human, Equally Entitled to Rights. Web. 27 July 2010.

Crawford, James. “Media, Stereotypes and the Perpetuation of Racism in Canada”. Educational Communications and Technology, University of Saskatchewan. Web. 27 July 2010.

Demara, Bruce, “Episode of The Border turns actors into activists. Two guest stars in show spread awareness of child soldiers’ plight”. thestar.com. Web. February 18, 2008.

Fulford, Robert, “Different show, same message; The Border retreads the CBC’s favourite theme:We’re better than Americans”. The National Post. Web. 12 January 2008.

Gorman, Bill, “Border Wars draws 2.9 million; natgeo’s highest ratings for a series”. TVbythenumber.com. Web. 12 Jan. 2010.

Gorodischer, Julian, “El mundo visto por Natgeo. Frontera: zona de peligro”. hipercritico.com. Web. 12 January 2010.

Invisible Nation, Policing the Underground, dir. & script Lindalee Tracey, prod. Peter Raymont, 1997. DVD.

Konrad, Victor, Heather N. Nicol. Beyond Walls: Re-inventing the Canada-United States Borderlands. U.K.: Ashgate, Border Regions Series, 2008.

McAllister, Kirsten. “Bridging the Geopolitical Divide at Home in Canada”, Programming Reality: Perspectives on English Canadian Television. Waterloo: Wilfried Laurier University Press, 2008: 325-342.

Minister of Justice. Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. Web. 27 July 2010.

Podur, Justin, “Defend the Border: Why CBC’s new show can only help “the bad guys””. killingtrain.com. Web. 5 May 2008.

Portal of North America. Web. 19 Jan. 2010.

Pratt, Anna, Sara K. Thompson, “Chivalry, ‘Race’ and Discretion at the Canadian Border.” British Journal of Criminology 48 (2008): 620-640.

Sadowski-Smith, Claudia. Border Fictions. Globalization, Empire and Writing at the Boundaries of the United States. USA: University of Virgina Press, 2008.

Stuart, Leigh, “Raymont on The Border”, Playback Magazine. Web. 27 July 2007.

Undefended Border, the. Dir. & prod. Peter Raymont, prod. & script Lindalee Tracey, prod. White Pine Pictures, 2002. DVD.

White, Patrick ,“Predator drones bring controversy to U.S.-Canada border”. Toronto Globe and Mail. Web. 19 Feb. 2009.